Tracing Ronnie Mackinnon

From The Western Front Association

Stand To! No 84 Article Extract

Princess Patricia’s Pals by Gordon MacKinnon

Introduction

Two young soldiers stand in a French house, leaning on a high stool to keep still whilst the film is being exposed, a photographer’s painted backdrop behind them. The house is in Bruay, a coal mining town of about 14,000 inhabitants in the French département of Pas-de-Calais, eighteen kilometres north-west of Vimy. Also then known as Bruay-en-Artois, today it is called Bruay-la Buissière.

Picture: Two Canadian soldiers in France, 1917.

Photo courtesy of Library and Archives Canada LAC e8319475 (Author’s collection)

‘Do you know your brother?’

The soldiers’ unique cap badges with the marguerite daisy indicate that they are in the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI). The taller soldier on the left is 157629 Private Ronald (Ronnie) MacKinnon and it is because of him that we know who the other soldier is. Ronald wrote two letters on 3 March 1917. In one to his father he wrote, ‘Just my usual to let you know I am alright and keeping well. I am enclosing a photo taken a few days ago. The pal along with me is Jimmie Rennie from Hamilton.’

In the other letter to his sister, Jean, Ronnie has a bit of fun, teasing her as to whether she will recognise him with his new moustache. ‘I am enclosing a post-card photo which I had taken out here. Do you know your brother? My pal is Jimmie Rennie from Hamilton.’ The shorter soldier is 785156 Private James Rennie.

The PPCLI War Diary holds the clue to the date of the picture. The PPCLI moved from the trenches of the La Folie sector of Vimy Ridge to the Rest Area huts at Mont St Eloi on 8 February and then to the Canadian Corps Rest Area at Bruay on 11 February. From that day to 22 March the unit remained in Bruay. To describe it as a ‘Rest Camp’ is inaccurate. In the six weeks the Patricias were away from the front line trenches, they trained almost every day on the large scale model of the enemy’s fortifications on Vimy Ridge.

Saturday 3 March, when the letter was written, was a rare half-holiday for the troops. The preceding Sunday saw a presentation of medal ribbons by the General Officer Commanding (GOC) of the 3rd Canadian Division, Major-General Louis Lipsett. No mention is made in the War Diary of either a Church Parade or half-day holiday but the routine was not to have battle practice on Sundays. Either that Sunday, 25 February, or the following day when the battalion went to the bathing area in the neighbouring village of Houdain, is when the picture was taken.

Divergent paths

Ronnie and Jimmie did not know one another before the war and became pals in the PPCLI. They had a few things in common. Both were twenty-three years old, both lived in southern Ontario and both had connections to the same part of Scotland. Jimmie was born on 23 October 1893 on the Isle of Bute. Ronnie was born on 27 August 1893 in Toronto. His grandfather, also named Ronald MacKinnon, was born on the Isle of Islay 60 k west of the Isle of Bute. Ronnie met his grandfather in Scotland for the first time in August 1916 when he had eight days leave after having spent two months recovering from wounds sustained on the night of 26/27 June 1916 whilst serving with the Royal Canadian Regiment (RCR) in Sanctuary Wood. Despite the fact that Ronnie had enlisted nearly eight months before Jimmie, each had spent only slightly more than three weeks in the trenches by the time they went to Bruay.

Divergent military paths led them to the same company in the same battalion. Ronnie had served three years as a part-time soldier in 48/Highlanders Militia of Toronto before giving it up in 1911. He married Lily Field in 1912 and they had two children by the time he enlisted in 81/Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) on 10 September 1915.

Picture: Ronald’s wife, Lily MacKinnon, and their children. Annie died in the ‘flu epidemic of 1919. Archie served in the Canadian Army in the Second World War. (Author’s collection)

Picture: Ronald’s wife, Lily MacKinnon, and their children. Annie died in the ‘flu epidemic of 1919. Archie served in the Canadian Army in the Second World War. (Author’s collection)

After preliminary training at Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, the battalion sailed on the SS Olympic for Britain, arriving on 6 May 1916. One month later the 81st was broken up and he was taken on strength of the RCR in Belgium on 10 June. The RCR was then in billets in Steenvoorde when it received 119 Other Ranks (ORs) as reinforcements. The battalion remained there, integrating the new additions, and returned to Trenches 63-74 at Sanctuary Wood on the night of 21-22 June. Ronnie’s career with the RCR ended four days later when he was wounded by shrapnel in the right thigh and right hand as the RCR was being relieved in the line by the PPCLI. Although the wounds were diagnosed ‘superficial’, in those days before antibiotics they were serious enough to be considered a ‘Blighty’, the soldiers’ nickname for a wound requiring treatment in Britain. After hospital treatment and convalescence he passed a Medical Board on 1 November 1916 and was placed in a draft to 3 Company PPCLI. He reported to his new unit three weeks before Christmas. The PPCLI was part of 7 Canadian Infantry Brigade, 3rd Canadian Division, along with the RCR and the 42nd and 49th Battalions. It was in Divisional Reserve in Mont St Eloi and moved to the Crater Line of the La Folie Left Sub-sector on Vimy Ridge ten days before Christmas. Ronnie was on sentry duty there on Christmas Eve and witnessed the impromptu Christmas Truce. ‘I had quite a good Xmas considering I was in the front line. Xmas Eve was pretty stiff, sentry-go up to the hips in mud of course. I had long rubber boots or waders. We had a truce on Xmas Day and our German friends were quite friendly. They came over to see us and we traded bully beef for cigars. Xmas was ‘tray bon’ which means very good’. On Christmas night he left to attend a three week course at the British Army School of Mortars, returning to the battalion on 12 January 1917. By the time the PPCLI arrived in Bruay to follow the Syllabus of Training for the attack on Vimy Ridge, he had been in the actual front line trenches for only thirty days. He was having a ‘good war’.

Jimmie Rennie attested on 14 April 1916 with 129/Battalion CEF in Dundas, Ontario. He had no previous military experience and had been a butcher in Hamilton, Ontario. Single and living with his married sister, he listed his widowed mother, Mrs Jean ‘Jennie’ Rennie, in Barrhead, Scotland, as his next of kin. After preliminary training, the 129th sailed on the SS Olympic from Halifax, Nova Scotia on 21 August. He was transferred to 124/Battalion (Pioneers) on 18 October 1916 at Bramshott and then to the PPCLI on 1 January 1917. Like Ronnie, he was not to spend much time in the front line before going to Bruay. The PPCLI spent twenty days in the trenches at La Folie Left Sub-sector in January and February and three days in working parties before going into Brigade Reserve at Mont St Eloi. Jimmie had only twenty days of trench experience exclusive of working parties.

The pals would have known each other for only a short time. Ronnie’s letters tell us that he was a rifle grenadier and perhaps Jimmie was too. It is very likely that they were in the same section.

Formidable mission

The intensity of the training at Bruay is indicative not only of the formidable mission that the Canadian Corps had been given at Vimy, but also of how inexperienced the soldiers were in the new tactics that had evolved. The PPCLI had suffered huge casualties since it arrived on the battlefield near Ypres in December 1914. By 1917 it had lost many of its original British army veterans and reservists who had emigrated to Canada. Its more recent volunteers rarely had previous military experience. On Saturday 20 March, 2 and 3 Companies returned to Dumbell Camp in the Bois des Alleux, Villers-au-Bois. Two days later they were back at the La Folie Sub-sector on the Crater Line between Grange and Tidsa Craters. They had been out of the line for forty-two days.

The period between their return to the trenches and the attack saw three raids on German positions, two practice barrages and several working parties. On 6 April – Good Friday – 3 Company proceeded to the Grange Subway (also known as Grange Tunnel). The tunnel and the jumping off trench is the section of line preserved today in the grounds of the Vimy Memorial. Ronnie wrote to his father from the Grange Tunnel: ‘Well, by the time you get this you will have read all about it and so will know more about it than me as I will only know what goes on in my own sector. I am a rifle grenadier and am in the ‘first wave’. We have a good bunch of boys to go over with and good artillery support so we are bound to get our objective alright. I understand we are going up against the Prussian Guards: the bigger they are the harder they fall! The Canadians have met them before and they remember it.’

The first wave of the attack was on a two-company front of 430 yards (394 metres) with Ronnie’s 3 Company on the left and 1 Company on the right. Their task was to capture the Intermediate Objective (Black Line) at the German position called Famine Trench. On the left flank of the PPCLI was 42/Battalion and to the right was the RCR. Except for the few men detailed as sentries, the deep tunnel protected the soldiers from the enemy shelling. Instructions came that they were to move to the Assembly Jumping Off Trenches (also referred to as the Observation Line) at 4:30 am on 9 April. They had a hot meal during the night in the Tunnel, the customary shot of rum in the trench, and a cigarette or two since smoking in the Grange Tunnel was forbidden. The secret PPCLI Operation Order No. 6 stated: ‘At zero hour [5:30 am] the intense shrapnel barrage will open on the enemy’s front line system, a short distance east of his crater posts and continue for three minutes. Small parties of the leading Coys will push forward into the craters and crater posts, if the barrage permits. At plus 3 the barrage will move forward in accordance with the Artillery Barrage Timetable…’ with lifts of 75 yards (68 metres) every three minutes. The attacking companies were given thirty-two minutes to take Famine Trench which was 675 yards distant (620 metres). The barrage would remain stationary 150 yards (137 metres) in front of Famine Trench for forty-three minutes while the position was stabilised and 2 and 4 Companies passed through on the way to the Final Objective. The schedule was kept.

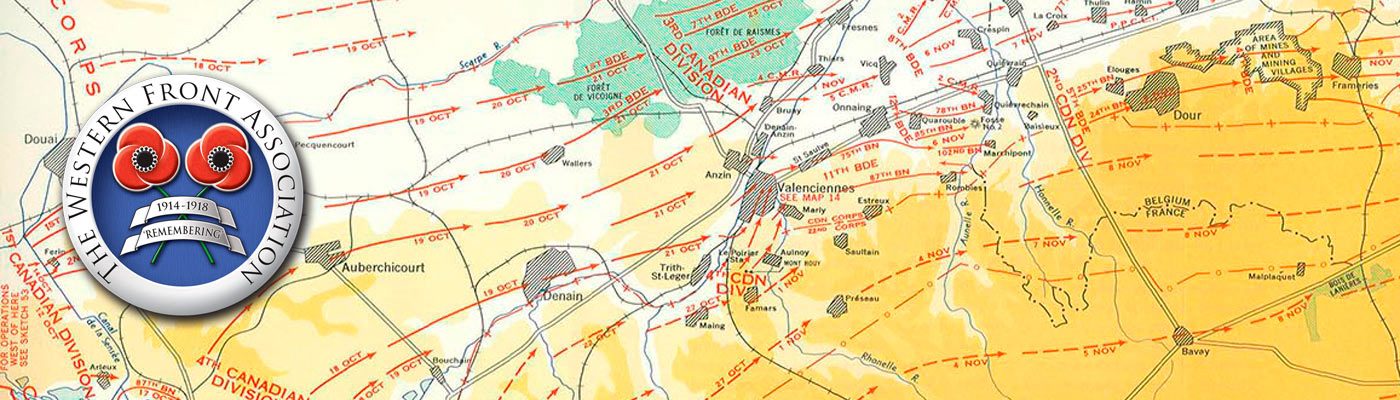

The action took place South East of the present day Vimy Monument to the upper left of the Blue Lines.

Onward to the Red Line

The infantry carried heavy loads. In addition to rations, full water bottle, rifle, bayonet, and haversack, each rifle grenadier had twenty No. 23 Mills Rifle Grenades, four smoke bombs with rifle attachment and a cup attachment and fifty rounds of blank ammunition for firing the grenades.

The two companies in the first wave climbed over the crater lip and attacked over shell churned ground towards their target, the Black Line at Famine Trench. The freezing temperature had hardened the mud somewhat and a sudden storm of sleet and snow blew toward the German sentries. The artillery barrage kept most of the German defenders in their dugouts. By 6:30 am the Patricias had taken Famine Trench, the Intermediate Objective, with very light casualties and by 7:40 am 2 and 4 Companies had occupied Britt Trench, the Red Line Final Objective on the eastern crest of the Ridge. The soldiers of 3 Coy occupied the left 215 yards (197 metres) of Famine Trench with 42/ Battalion on their left flank.

Although the casualties during the initial stages of the assault were low, they increased when enemy artillery realised that the Canadians had taken the two German lines. In addition, the 4th Canadian Division on the left flank of 42/Battalion was behind schedule in taking Hill 145 where the Vimy Memorial is today, and German machine gunners and snipers inflicted many casualties from that position. For the two-day operation the PPCLI casualties were three officers and 54 ORs killed in action, seven officers and 142 ORs wounded (six of whom died of their wounds), and ten missing. One of the 3598 CEF fatalities was Private Ronald MacKinnon and one of those missing was Private James Rennie. Ronnie’s body was exhumed at S.23.c.4.5 according to the Brown Binders. This map co-ordinate is the point in Britt Trench Final Objective where the PPCLI right joined the RCR left flank. He was buried in Bois Carré Military Cemetery (VB2), in the village of Thélus.

Picture: Bois Carré Military Cemetery. Photo Courtesy of Simon Godly, Spring 2008

Picture: Restored Vimy Memorial Panel. Photo Courtesy of Simon Godly, Spring 2008. NB Serial numbers are only engraved if there are two identical names.

Jimmie is first recorded on his Casualty Report as ‘Wounded in action’ and then as ‘Wounded and missing after action’ and then as ‘Now Reported killed in Action.’ His remains were never identified and his name is one of those 11,285 missing Canadians commemorated on the Vimy Memorial.

Pals for three months in 1917, the two soldiers are still together on Vimy Ridge.

Notes on Sources

The MacKinnon Family letters are online at www.canadianletters.ca The War Diaries of the PPCLI and RCR are online. For help in locating these and the Personnel Files of Ronald MacKinnon 157629 and James Rennie 785156, go to www.cobwfa.ca and click on RESEARCH.

Library and Archives Canada: RG150 Acc.92-93/314 Brown Binder No. 217. The Brown Binders list the known trench map co-ordinates where remains of CEF fatalities were found. They are not online. Thanks to member Floyd Low for telling me about the existence of the Brown Binders, for obtaining the relevant pages, and for the map work using the excellent Linesman Software. He also converted the map co-ordinates into GPS co-ordinates. Ronald’s body was exhumed at 50°22.407’N, 2°47.192’E.

Stephen K, Newman, With the Patricia’s Capturing the Ridge, Bellewaerde Publishing, Saanichton, British Columbia, 2005

Gordon MacKinnon is the nephew of Ronald MacKinnon. He is Secretary and Vice Chairman of the Central Ontario Branch of the WFA.